Visual Lexicon

with Basil Kincaid

I Ain't Got Time for the Blues. 2017.

Photo courtesy of the artist

[Originally published October 31, 2017]

He began by drawing tiny circles, “smaller than a grain of rice,” on stacks of printer paper, and it was all Basil Kincaid drew for some time. At first, his parents didn't quite understand the repetitive meditations of their firstborn, but they soon realized that their three-year-old son was already captivated by this thing called art, whether even he knew it or not. Now though, at the age of 30, Kincaid has fully embraced his calling as an artist.

When I ask Basil Kincaid if there is a difference between Basil the person and Basil the artist, he responds, “the work is my life and my life is the work.” And he’s right. Everything I have ever known, heard, and observed about Kincaid is related to his art practice. For Kincaid, art is a means of honoring family and tradition, the beginning of a process of healing from trauma the world inflicts upon us, and—as it is for many of us cultural workers—a vital method of viewing and processing our world.

It takes more than one person to do anything.

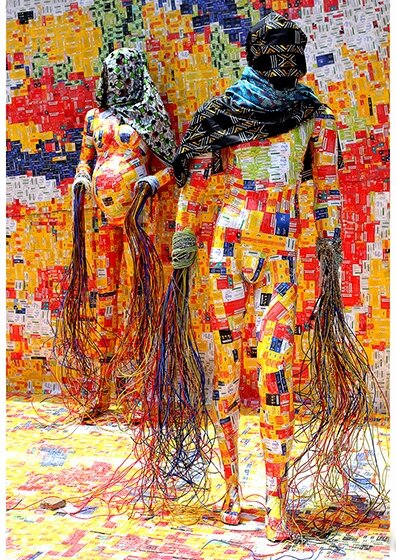

His latest projects, including Reclamation, Reclamation 2: Ghana: “A Call Home,” and a series of striking quilts, all call back to the space of honoring, observing, and processing. Reclamation and Reclamation 2, both projects with St. Louis-based artists Damon Davis and Eric “Prospect” White, honor and reclaim elements of the past, both figurative and literal, reshaping them into new forms that drive their vision of the future, as Kincaid writes on The Reclamation Project:

The Reclamation Project… focuses on valuing community, diversity, heritage and inclusion all through a lens of creative recycling. We direct our focus on reclaiming the debris of our collective past and present as a way to forge a new future. Using found objects, we recycle creatively to address the interplay between poverty, consumerism, and environmentalism. Reclamation also focuses on identity, exploring how ones surroundings effect their perception of self.

Starla, 2014.

Image courtesy of artist.

The Reclamation Project also deeply values how the work both reflects and interacts with the community, with “community” serving as spectator, inspiration, and participant. Kincaid has carried this multifaceted approach to his most recent quilting projects, inspired by the beautiful works of necessity that adorned the beds of his grandmother’s home. Kincaid saw the quilts as “abstract art at its highest form.” Recalling how he and his brother Matthew frequented museums with their mother, Kincaid notes how those family quilts could be in any museum. He also looks at his past and present work as a way of fully acknowledging the value, beauty, and importance of culture outside of the Western (read: white, European, and mostly male) cannon.

“If we are guiding the course of our cultural production, the inspiration becomes extremely important.” He became more critical of the art history he was taught to appreciate, that which was seen as the base, the norm, and reconsidered what he “want[ed] to present to future generations as the hallmark.”

That is what landed him on quilting, what Kincaid calls the “visual lexicon of our environment, culture.” But, it took time for Basil Kincaid to get to this point of confidence, and of clarity, about his work.

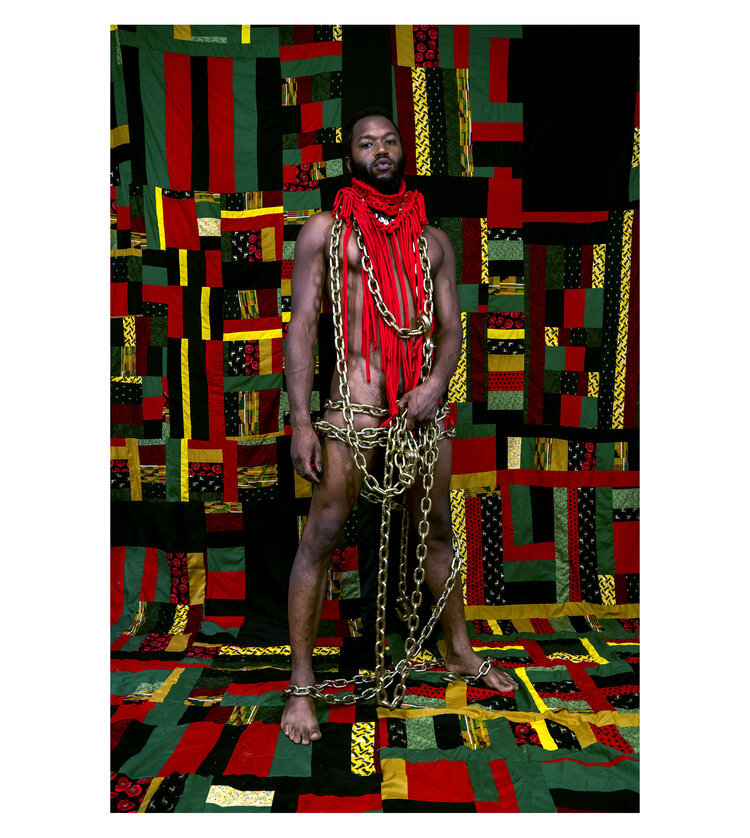

Black Excellence: A Song For My Mother: Pt. 1. 2017. Image Courtesy of the artist.

While Kincaid always knew he wanted to be an artist, he was not always certain that he had the business acumen or the talent to turn his passion into a career. His family—mother, father, and brother—supported Kincaid’s artistic talents throughout this entire life, including his decision to study art in college, but not without sage advice.

“My mother told me, ‘You know you are going to have to work way harder doing that. No set pathway. You don’t have a safety net. You’re operating a business, and have to be serious about your time, and dedicate yourself more than you would any other job because it’s all on you.’”

She also reminded him that without a set salary and a boss giving direction, it was up to Kincaid to be a self-starter and to stay motivated. This of course included learning how to monetize his art.

“Monetizing something personal seems blasphemous,” he tells me, “but if it’s a career, you gotta do it.”

These traits of hustle, ambition, and resourcefulness were all instilled in Basil Kincaid as a child, as he notes. He frequented the farmers’ market with his grandfather, learning how to sell vegetables; he discovered how to make-do with what they had on his grandfather’s farm; and unending belief and support from his parents filled him with self-confidence. This hustle and confidence carried him through elementary school, high school and college. Kincaid originally went to Colorado College to major in economics and finance, intending to be an investment banker but also planning to do visual arts during the course of his studies. His parents wanted Kincaid to do what he loved, but Kincaid was also laden with the perception that, “if you’re going into the arts you will struggle your whole life, no one will know who you are, and you will be poor and die alone.”

It was fairly easy for Kincaid to sell art in college, but returning to St. Louis with a liberal arts degree in a weak economy left him with few options. He couldn’t get arts jobs and worked at a grocery store to make ends meet. He did, however, start an afterschool art and fitness program, and began to make the rounds in the city’s art community with the help of Kaveh Razani, proprietor of Blank Space. By taking notes for Razani during meetings, Kincaid met the many young black artists he had hoped to connect with in St. Louis: people doing it their own, maybe working a few days at another job, but were “hungry for their passion.” He promoted his name by creating graffiti art on Airmail stickers and selling them for $10. While he sold out of his first batch, he didn’t make a great sum, but “it felt good knowing that people liked what I made.”

Later, Kincaid got an opportunity to teach art at a middle school in New Orleans through his brother Matthew, who was also teaching there. As Kincaid puts it, this teaching opportunity was his “first real job.” He loved the kids but spent all of his creativity on them. Towards the end of the his year of teaching, he received an email from Arts Connect International regarding an opportunity to explore and connect—through art—his passion for social justice from the United States to the international place of his choice, which turned out to be Accra, Ghana. Kincaid knew he wanted to go to West Africa, the likely home of his ancestry, and the home of atrocious dungeons that tens of thousands of slaves passed through prior to entering the Middle Passage. In Accra, he met and collaborated with rising star artist, Serge Attukwei Clottey, who helped him acclimate to his new temporary home.

Early in his residency, Kincaid noted that Ghanaians connected through phone on the pay-as-you-go model, which through phone cards, left a physical record of people’s connectivity. He tells me “each network is a different color,” letting you know “which company has which market share in the area.” When he researched the companies, he found that most of the profits went to Western countries, “colonizers,” with precious little returning to the African Economy. Kincaid calls them “Cycles of economic extraction: of people, resources, money.” These phone cards compelled him to consider the concept of “material memory” and ultimately led him to quilting. Kincaid also incorporated labels of plastic water bottles into his quilting practice, exploring the issues of water rights and related energy crises.

Our Children Are Now Born Online. Outdoor Community Installation | Labadi Township, Ghana 2015. Image Courtesy of Basil Kincaid.

Kincaid showed the fruits of his residency through several shows around the country, which helped propel his name and talents in art circles, especially in St. Louis. Afterwards things slowed down, and he felt compelled yet again to find a job to make ends meet. His boss, though, encouraged him to focus full-time on art, to “lean into it.” One and a half years later, he is thankful he followed her advice. “I’m making enough money to support my practice and myself."

Recently, Kincaid completed a large quilt for a corporate commission. The president of the company was one of his first patrons and returned to him to provide art that reflects the company's re-branding efforts. I assume that this quilt, as is the case with many of his other quilts, is created not by Kincaid alone, but with the help of hands from his community: friends, loved ones, interested strangers. He tells me that “it takes more than one person to do anything,” and his work is a beautiful embodiment of that philosophy.

Follow Basil Kincaid on Instagram! It's pretty fantastic.